As I was writing another post on Private Equity (here), and one of the papers mentioned in the post (Phalippou, 2020) was highlighting the issues of “since-inception IRRs” of old Private Equity firms, thought it was worth touching on that issue separately.

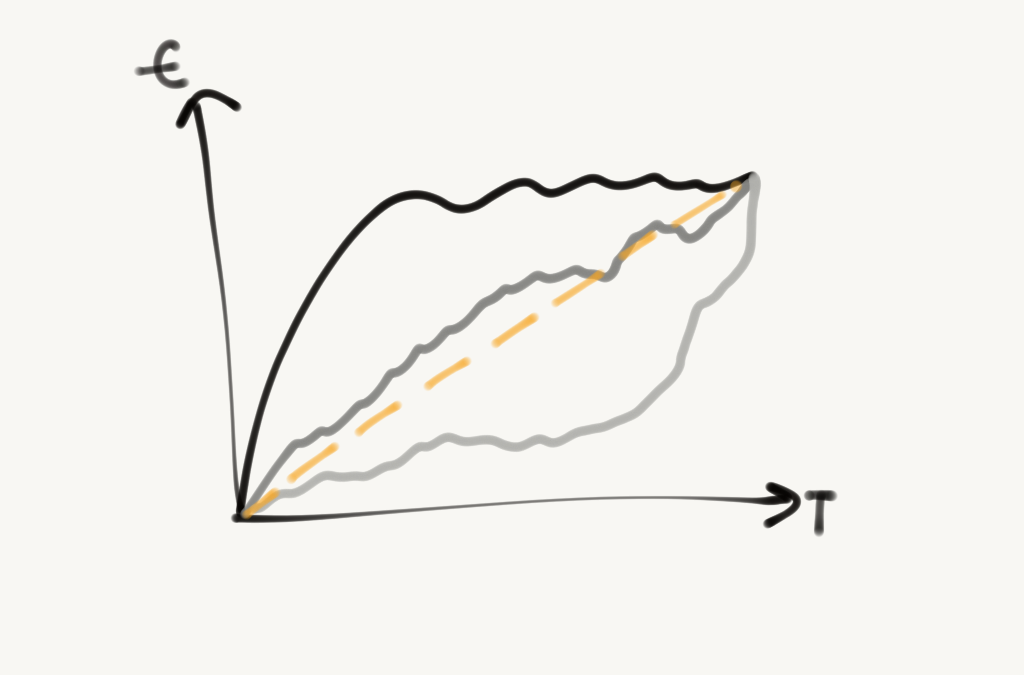

This post is mostly a warning for the general public about advertised long-term IRRs, not only in the PE space, but applied to any investment product. One long-term performance number does not mean much, sometimes it doesn’t even mean anything at all: what matters more is how the returns over multiple periods are distributed. A fund/manager who performs exceptionally well at the beginning of his track-record will enjoy a very high average performance for many years unless he generates very large losses.

The question for the investor is: is such an average performance representative of what one could expect for the future? Not only PE firms mentioned in the paper above, also hedge fund managers who profited massively from the 2007-2008 subprime crisis with big bets that reportedly generated returns of over 100%, see Paulson’s or Bass’ top-performing vehicles, just to deliver weak or at least far less impressive and highly volatile performance in the following years.

And even look at the performances generated by Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway: although the extraordinary long-term track-record is clear, the returns between 1965 and 1985 were 28.7% p.a., while from 1986 to 2020 averaged 15.2% p.a., yielding a CAGR since inception of 20%. Compare it against “only” 9.1% since 2000 … vs. 6.6% for the S&P 500, though.

How true is the usual disclaimer “past performance is no guarantee of future results”, and how often it is neglected in the hope for (or temptation of) riches.

Sources:

– “Hedge Fund Manager Kyle Bass Declares War on Drug Prices”, Institutional Investor, October 2015

– “Paulson’s Advantage Plus Fund Returned 142% Since 2007”, Insidermonkey, December 2011

– Berkshire and SPX performance numbers from Berkshire 2020 annual report yearly returns table