Should we expect in the coming years and decades conflicts and price shocks linked to battery materials just as the world has experienced with oil and gas in the last 50 years?

Commodities of the past and future

Two decades ago, when the first big wave of renewable energy investments started, many were imagining a world with solar panels and wind turbines powering a significant chunk of our economies. With one big bubble (bursting) in between, that scenario pretty much materialised. Europe went from 9.6% renewable in 2004 to 22.1% in 2020, based on Eurostat data. Today, two decades after, it has become mainstream to imagine a world almost fully powered by such technologies, also thanks to batteries and other energy storage systems. Europe’s ambitious target for 2030 is to more than double this to 45%. Despite the fact that in 2021 coal-based electricity generation increased strongly, reaching a new record, and we may well end 2022 with another strong increase (also due to gas-to-coal switching), it makes a lot of sense to still dream of a renewable-powered world in a few decades, despite some threats: metals availability, metals geopolitics and carbon-capture technologies.

Drilling and mining tend to generate negative vibrations in the general public. Many do not want to use oil or gas anymore, which is fair enough. But if we want a renewable-energy driven future, we will need to use metals like lithium, a key component in battery technologies, copper, etc. We cannot wait until new revolutionary technologies will be available, if we want to be consistent with climate goals. For large scale applications it could make sense to use mechanical storage systems, instead of batteries, but for cars and other smaller-scale applications, batteries and, therefore, metals will be necessary in the foreseeable future.

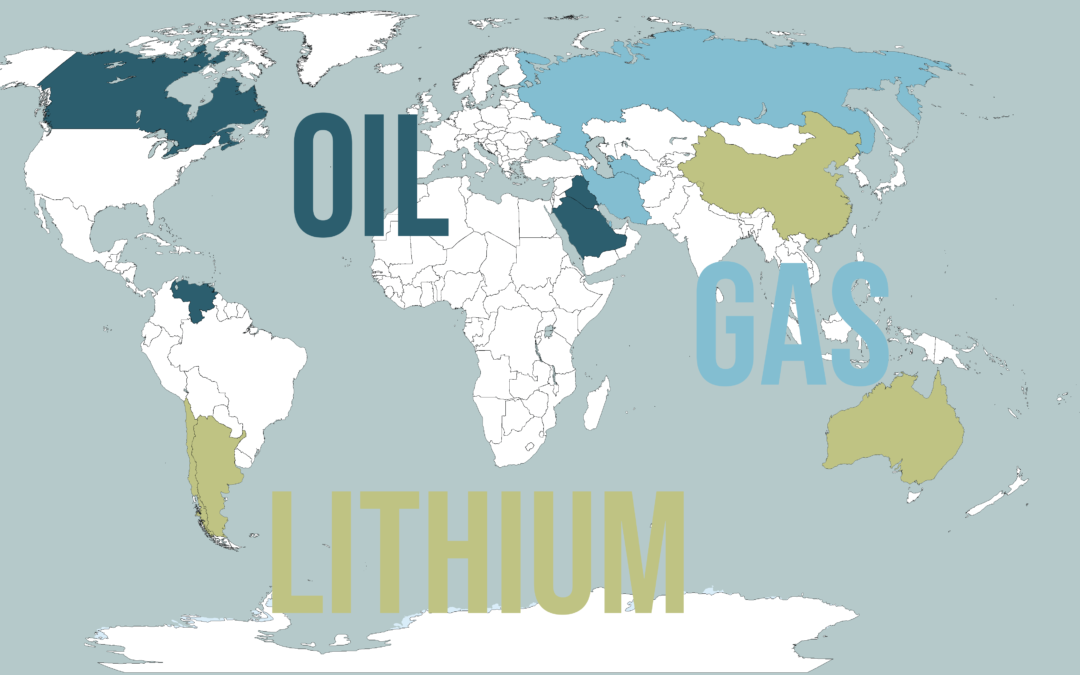

Let us compare in the table the countries with the largest oil, gas and lithium reserves in the world.

| Oil | Gas | Lithium | |

| 1st largest | Venezuela | Russia | Chile |

| 2nd largest | Saudi Arabia | Iran | Australia |

| 3rd largest | Canada | Qatar | Argentina |

| 4th largest | Iraq | Turkmenstan | China |

There is already a significant difference between gas and oil leaders, but the difference is dramatic when we look at Lithium. Totally different geographic regions controlling key resources of the future.

Energy conflicts

Energy commodities have historically been linked to major geopolitical events. Let us summarise some key conflicts over the last 50 years that were linked to oil (and the last one predominantly to gas and to a lesser, but still very significant extent, oil):

- 1973 Yom Kippur war, where OPEC countries implemented an embargo against countries supporting Israel. This led to oil prices quadrupling by the beginning of 1974.

- 1979 Iranian revolution, with oil prices more than doubling.

- 1980s Iran-Iraq war, with an aggressive Saudi Arabia oil marketing policy which led to an oil price collapse in 1986.

- 1991 First Gulf war, led by the US against Iraq in response to the invasion and annexation of Kuwait, which made oil prices double, in the so-called 1990 oil price shock.

- 2003 Second Gulf war, the one originally and officially justified by Iraq’s never-to-be-found weapons of mass destruction. After production declines before the war, Iraq’s oil production more than doubled by 2019 vs. pre-war levels, with no dramatic apparent impact on oil prices.

- 2021 gas price shock, starting in 2Q21 and accelerating until very recently, which we are very much aware of.

The causality is not always easy to prove, like in the case of the 2003 war against Saddam’s Iraq. And it can go both ways: conflicts can lead to energy crises and conflicts can be initiated to resolve energy crises. For completeness, energy crises can also be leveraged to initiate conflicts. That said, we can see an overlap between major conflicts and countries, especially developing ones, with major energy resources. Being a resource-rich country is not automatically a blessing. Quite the opposite, based on the theory of the Dutch Disease. But armed conflicts are in a different league compared to the mostly economic implications of the Dutch Disease theory.

Does humanity never learn or are we confronted with inevitable dynamics? Probably the inevitable dynamics arise exactly from our human nature.

Is lithium the new oil? Well, there are differences. If you are Chilean, Argentinian or Australian you may think that’s at least a positive piece of news.

There are some differences

First of all, we should expect to recycle a lot of lithium (and other key electrification metals) in the long-term, as companies have already been investing in processes and facilities and will scale up these operations. This is significantly different compared to oil and gas, as we take oil and gas out of the ground, we burn them, and bye bye. And this is a good thing.

What is likely to become problematic, however, is that if we really want to transition quickly from fossil to clean(er) energy, someone will need to mine a lot of lithium (and other metals) very quickly. Smooth and gradual transitions are generally preferred, as booms also lead to busts and there are always unintended consequences. We think we can manage transitions, but we actually can’t foresee everything and there are always risks and issues we have ignored because of our human limitations. Overconfidence bias and planning fallacy should ring a bell. Not sure whether AI will ever be able to solve this problem. There are easier things in life than getting lithium out of the ground and into a battery. Tweeting, making bold claims, meeting in Davos, are just a few. Also, at some point, if demand is too large relative to supply, prices skyrocket. This stimulates new supply but also temporarily slows down demand and therefore the speed of the energy transition.

Commodities are highly cyclical and as a producer you may find yourself in a position of strength today while in a few months you might be in a very weak position in terms of bargaining power. In the first half of this year, OPEC has been in a pretty strong position. OPEC countries have in some cases been courted by Western powers who needed their commodity at reasonable prices in order to raise their citizens living standards, while in other cases they have been bombed. Will this happen also with countries like Chile and Argentina? Let’s hope not, of course. Should we imagine a South American clean-energy-metals cartel similar to OPEC down the road? Why not, if there is the will to collaborate. There would be obviously pros and cons, but the ability to stabilise the market could be an important factor. Especially considering that the future trajectory of demand is extremely difficult to predict.

Another important difference between oil/gas and transition metals is that the world can reduce the urgency of mining lithium and other metals exactly because we are confronted with a transition, and not a steady-state operation. We need oil and gas every day, continuously, if we want to keep our economies running. Under the assumption that while transitioning, we can maintain spare capacity in both oil and gas, we have some margin to manoeuvre should our economies be confronted with a sudden reduction in the supply of key metals. Key questions will be: how long can the environment wait until we transition and what will be the cost of a slow, clean (referring also to the sourcing of the metals) and smooth (with no metals-related conflicts and crises) transition?

Conclusions

We are currently confronted with a dramatic shift away from fossil fuels and into energy-transition metals. It is impossible to forecast with accuracy how the transition will look like, in terms of speed and problems down the road. Governments will play a key role in shaping the transition, and they will have a huge responsibility to design rules and targets that are achievable, along the whole, very complex value chain. That is a strenuous task, and we should appreciate the complexity and related risks. As history tried several times to teach us with energy commodities, geopolitics are a key factor. Apart from the investment implications, what will geopolitics in the era of clean-energy-metals mean for countries holding the resources that are key for the world economy we are imagining? This will have real impact on people’s lives, not only on financial instruments, be them equities, commodity futures, emerging market bonds and currencies.