Already at the end of March the U.S. was reported considering a global minimum tax rate. If your national debt is going out of control and are at risk of losing competitiveness, well, it makes sense egoistically to try and make other countries less competitive, less attractive. At the same time, the “race to the bottom” in terms of corporate tax rates, which the U.S. declared a fight against, sounds sensible, especially when national debts are massively on the rise after Covid. In theory, it is also a matter of justice when it comes to balance workers’ and companies’ tax rates and burdens.

The “historic” deal

Over the weekend, the U.S. managed to get the idea through at the G7. The UK’s Chancelor of the Exchequer proudly tweeted about the “historic agreement […] requiring the largest multinational tech giants to pay their fair share of tax in the UK”. When one considers that British Overseas Territories remain at the top of the list of tax havens, as reported by Tax Justice Network, with corporate tax rates as low as 0%, one wonders: is this really a massive change of direction, also for the UK, or when the Chancelor mentions “tech giants”, he really means only tech giants taking advantage of tax deals in countries like Ireland, and not the other offshore businesses in BOTs or Crown Dependencies like Jersey with taxes ranging from 0% to 10%?

How will “history” look like?

The next step is getting this idea through at the G20 and then to actually implement it in the real world and not only on Twitter. The basic implementation rules highlighted on Twitter, based on factors such as size and margins, and later subject to a re-allocation mechanism, show that there is a risk that the actual implementation may end up being less “historic” than one initially believed.

The NGO group Oxfam already expressed its criticism about the deal, noting how the 15% proposed tax rate is not far from the (standard) level offered by some of the tax havens allegedly targeted by these measures.

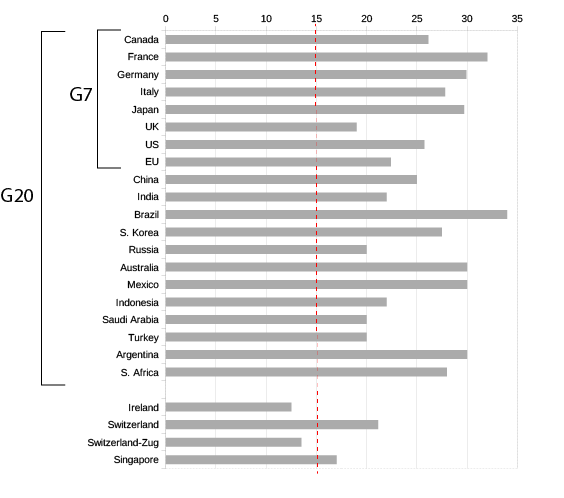

In the chart below I’ve collected the numbers on corporate income tax rates for G7 and G20 countries* and compared them to those in Ireland (one of the jurisdictions used by big tech to reduce tax rates) Switzerland (highest rate and canton of Zug), Liechtenstein and Singapore (the closest to an “Asian” Switzerland). Is 15% really revolutionary or rather “disappointing” as claimed by Oxfam? One should note also that tax systems are often complex and allow for more or less complex deductions such as for R&D activities, special tax breaks, so companies may already pay lower tax rates than the standard rates applicable in theory. Especially when we look at how the famous Ireland-Apple tax deal was structured, it was not about the ordinary tax rate, but rather a special deal and structuring (see EC).

Corporate Income Tax Rates

* Sources: from OECD statistics (2021 where available), national tax authority web sites when not available from OECD 2021, and from global OECD 2019 database when neither of the previous sources was directly available

So the devil is in the details of the implementation (as usual) and unless the deal is really global and ends up eliminating also a broader set of tax advantages like in jurisdictions such as the UK territories with 0% tax rates, it is not clear whether it deserves the label “historic”, yet.

Competitiveness

Another question is: what does this concerted effort actually say about the competitive position of the global tech giants, is it compromised or is taxation only a marginal issue for their business model, especially if only high-margin businesses are affected?

Would countries like Switzerland remain sufficiently competitive on multiple fronts if their edge on the tax side is eroded?